I sit here, at home in an ashram, and type away at the white screen. Crawling like black ants out of a crevice, the words that arrive prove unreliable. They force me into spaces that I’d rather not touch, those hidden crevices in the house where unknown creatures lurk. From Goa, the end of my great Escape, I returned to a Madras metamorphosed into Chennai, then back, back to this little room. The Great Escapes in my life have been flights off a cliff, headlong into empty space. I flee into an unknown land, forced to leave routines of thought and being behind, a journey without companions or plans.

Twenty years or so ago, I had accompanied my cousin in her army jeep to Goa without absorbing much of the surroundings. Then, after the death of a god, suffocated by the social strictures of a spiritual community without its guide, I ran again. The sea called me, the memories of long, empty Goan beaches. Marked by its dependence on tourist trade, Goa nurses a risky reputation. Indian newspapers report murders, rapes, drug traffic in the state. But, after being there for almost 3 months, I find it safer and less indian than the other states in the country. As with most of its counterparts in other parts of the world, tourist trade in Goa makes for a laissez-faire culture.

Breaking out of the ashram, I seek yet for the lurking, uncertain magic of god, for a being whom death has freed from constraints of society or religion. A symbol. Where do I run to? To a place that is the obverse of a structured community, to tourist haven. Traveling today is easy. We board buses, trains, cars, and journey to places we have researched thoroughly. Trawling through sites like TripAdvisor, I realized that hardly any place on the globe remains unreviewed by previous travelers. Comments, reviews and blogs render the destination familiar before I set foot outside my door. We live in a world of déja vu, the already seen, already reviewed topography.

Staying for almost three months in Goa, I grow another skin. I become Goan in part. My return here to Puttaparthi asks that skin to be peeled off, a process more than cosmetic. My tan has to fade. I have to dress differently, to cover my newly sensitive skin with more layers against the sun, and social morés. Despite the ease of my journey, travel has turned me foreign to the self who lived here. Coming back ‘home,’ to a place I’ve lived in, for almost seventeen years, I am blessed with a sense of difference. Puttaparthi, for fifty years of my life has evoked a sense of wonder in me, symbol of a world beyond human logic. Now, the spell has broken. Magic exists, yes, but not here for me. Through my childhood years, beyond memory, I remember the journeys to this place, always with a sense of expectancy, a churning stomach, premonitions of marvel.

Driving down, through the heat and the arid thorn bushes, we packed the car with necessities–rice, kerosene stoves, pots, pans, dishes, bedding, sheets, towels, buckets, mugs and other stuff now forgotten. Trailing two young kids in her wake, my Mum had to plan for all contingencies. Our car, a 1961 Ambassador, bumped valiantly over rutted, pot-holed non-roads. When in Madras, I looked for Ambassadors, those solid iron boxes on wheels, but only spotted them seldom.

[Ambassador or Amby – the first car to be manufactured in India, has been running on the Indian roads since 1948. Based on the British Morris Oxford it is now made by Hindustan Motors (HM)]

[Ambassador or Amby – the first car to be manufactured in India, has been running on the Indian roads since 1948. Based on the British Morris Oxford it is now made by Hindustan Motors (HM)]

Sober grey white, with steel detailing, our Amby was a bit different to one in the image. Sporting a catchy license plate with the number, MSR 100, the car, over the years it stayed with us, developed a character all its own. Journeys to Puttaparthi, the landscape of semi-desert, were its forté: MSR 100 hardly ever broke down along the way. We’d see cars of lesser determination stranded with their bonnets open, often spouting grey fumes of smoke as we chugged by.

Petrol stations were sparse and far between, so Dad had to watch the miles between. In the monsoons, old MSR 100 would face a different problem than overheating as freak floods would block the road. But, built to withstand indian terrain, the Amby’s ground clearance contested the SUVs of today. Without a sputter of protest, MSR 100 pushed through the rising water. Today, the Amby’s rusted iron number plates stand memorial just before the front door of my ashram apartment, decorating my garden.

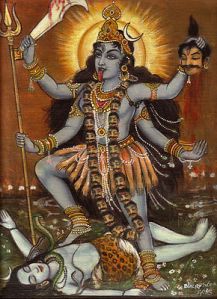

Having lived so long in an ashram, I absorbed the Hindu respect for all beings, animate and inanimate. Swami often remarked that even dead bodies have atma or consciousness. Tempted to believe that MSR 100 lived, fought, and had a being, I particularly notice the Hindu beliefs about vahanas or vehicles [Vāhana from sanskrit–that which carries, that which pulls].

The vāhana may be considered an accoutrement of the deity: though the vāhana may act independently, they are still functionally emblematic or even syntagmatic of their “rider”…. Vah in Sanskrit means to carry or to transport. [wikipedia: vahana]

Living here as I did, hindu-catholic mongrel as I am, brought up by intellectuals who never bothered to teach their kids any religious rudiments, I found my own interpretations for rituals unknown, as, for example, the worship of vehicles during Ayudha Pooja in September/ October. As a child (and perhaps even now), I simply believed that MSR 100 was a special vehicle with a soul of its own. If my god and Merlin said that atma or consciousness resided in all things, animate and inanimate, why not a car, particularly a car like MSR 100? Movies like Chitty, Chitty, Bang, Bang reinforced my views. And what about Stephen King’s Christine? She may be a car of evil intent, but ‘Christine’ lived and was destroyed. The cars that transport us, or trains, or buses, or planes, may be put together by us with steel, wires, rubber, and fuel, but they are greater than the sum of their parts.

As a child (and perhaps even now), I simply believed that MSR 100 was a special vehicle with a soul of its own. If my god and Merlin said that atma or consciousness resided in all things, animate and inanimate, why not a car, particularly a car like MSR 100? Movies like Chitty, Chitty, Bang, Bang reinforced my views. And what about Stephen King’s Christine? She may be a car of evil intent, but ‘Christine’ lived and was destroyed. The cars that transport us, or trains, or buses, or planes, may be put together by us with steel, wires, rubber, and fuel, but they are greater than the sum of their parts.

That special magic of life with Swami opened my eyes. I wonder at the syntagmatic relationship between humans and created objects, the part (the car) leads to the whole (the ‘owner’). MSR 100 sat for years in front of our house “Sai Jyothi.” The house itself was a symbol, built for Mum by Dad. Theirs was a hard union: Catholic and Hindu, my Dad and Mum had been separated by parental edicts for twelve years. Ironically, Dad died a couple of years after moving in. But, Mum loved the house: it gave her the space and security she needed to collect her thoughts, and her actions. After Dad died, she sold her small car, the Fiat, but kept the Amby. Later, MSR 100 took me to college way out in the boondocks of Andhra, past Puttaparthi, into a dry dusty town/ village. At the last, when Mum died, decades after my Dad, MSR 100 carried me back and forth to hospital. It carried me back to “Sai Jyothi” one early morning when she breathed her last.

Another decade later, when my Merlin/Swami declared that the house was to be sold, I returned to see MSR 100 squatting on its deflated tires, stubborn to the end. Opening its bonnet to check on the engine, I beheld the skeletons of rats and mice decorating its bowels. I sold the car for scrap. When the they came to take it away, they towed the Amby by its back axle, its nose to the ground. Watching, I broke down and wailed for the first time on my return to Madras. MSR 100 departed in protest, dragged by its heels to be torn apart for scrap. The number plates, rusted with missing letters, bide still among the green tropic plants. Entering or leaving my flat here in the ashram, I notice the plates and remember the spirit of the past, my MSR 100, guardian of childhood, harbinger of journeys.

Entering or leaving my flat here in the ashram, I notice the plates and remember the spirit of the past, my MSR 100, guardian of childhood, harbinger of journeys.

As a child, I used to creep out of the back door of the bath room, out to sit under the Neem tree in the night quiet. [http://www.organeem.com/neem_tree.html] Sitting there, I would let the minutes and hours slip away, breathing in the sentience of non-human earth. Way back in the bowels of the house, caught by human anxiety, Mum would hunt for me, “Grie, Grie, where where are you?”

As a child, I used to creep out of the back door of the bath room, out to sit under the Neem tree in the night quiet. [http://www.organeem.com/neem_tree.html] Sitting there, I would let the minutes and hours slip away, breathing in the sentience of non-human earth. Way back in the bowels of the house, caught by human anxiety, Mum would hunt for me, “Grie, Grie, where where are you?” Only now, sitting in this little semi-open patio, with the Rain tree’s [Albizia Saman] branches spreading overhead in the green company of shrubby foliage, I wake from the thrall of an unplanned two hour sleep to chanting from the hall, and feel a sudden breath from the child I was. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albizia_saman]

Only now, sitting in this little semi-open patio, with the Rain tree’s [Albizia Saman] branches spreading overhead in the green company of shrubby foliage, I wake from the thrall of an unplanned two hour sleep to chanting from the hall, and feel a sudden breath from the child I was. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albizia_saman]

Even in

Even in

[One of artist Nickolay Lamm’s images of what the

[One of artist Nickolay Lamm’s images of what the  [The image shows two fishermen carrying the catamaran out to sea, but the boat seen is the nearest I could find on Google to the log boat that I saw.]

[The image shows two fishermen carrying the catamaran out to sea, but the boat seen is the nearest I could find on Google to the log boat that I saw.] Living without possessions heralds freedom for me. Is this because I see a breathing universe which holds all beings, animate and inanimate, equally? If humans are merely one species amongst others, how may we, humans, ‘own’ things and ensure security? Aren’t we perpetually dependent on the goodwill of a cosmos with its cycle of death, flood, hurricane, famine, tsunami? The pagans saw gods everywhere, in every tree, rock, and stream, and sought to placate them with offerings, human, animal, or plant. In today’s industrial world, danger lurks in every corner, but, so equally, does joy. Both unsought for, each seizes us most when we are unaware. How do we assure of ourselves of either, though we seek them under umbrellas of adventure or happiness?

Living without possessions heralds freedom for me. Is this because I see a breathing universe which holds all beings, animate and inanimate, equally? If humans are merely one species amongst others, how may we, humans, ‘own’ things and ensure security? Aren’t we perpetually dependent on the goodwill of a cosmos with its cycle of death, flood, hurricane, famine, tsunami? The pagans saw gods everywhere, in every tree, rock, and stream, and sought to placate them with offerings, human, animal, or plant. In today’s industrial world, danger lurks in every corner, but, so equally, does joy. Both unsought for, each seizes us most when we are unaware. How do we assure of ourselves of either, though we seek them under umbrellas of adventure or happiness?